Pacific Tarn from the south shore, looking northeast.

Pacific Tarn Trip Report

(C)Copyright 2002 by Carl Drews

Last update: September 30, 2014

Contents:

Abstract

The Trip

Measurements

Does it Freeze Solid?

The Next Step

If You Go

Thanks To

Other News

This web page describes a scientific expedition to "Pacific Tarn", a high alpine lake below Pacific Peak in the Tenmile Range near Breckenridge, Colorado. A few other people and I had long suspected that this lake was the highest lake in the United States. "Pacific Tarn" is my unofficial name for the lake; it is not listed in the USGS database here:

http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnis/web_query.gnis_web_query_form

I couldn't find a name on any topographic map, although "Pacific Tarn" is bigger than several named lakes nearby on the same quad map. That's gotta be worth something.

"Pacific Tarn" is at 13,420 feet, and this makes it higher than the highest named lake in the United States, which is Lake Waiau in Hawaii at 13,020 feet near the summit of Mauna Kea. The goal of the expedition was to visit the lake, verify that it still exists, measure it accurately, and gather enough information to substantiate our claim that it is the highest lake in the country. Perhaps with enough data, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names might accept a proposal to name the lake and add it to the national database.

Of course, any excuse to go hiking up into the mountains with friends is sufficient. Or no excuse at all.

My friend Paul Fearing is a trip leader with the Colorado Hiking and Outdoor Society, more commonly known by its initials as C.H.A.O.S. Paul organized a trip to visit Pacific Tarn over the weekend of July 13-14, 2002. Fourteen people signed up for the trip, which demonstrates the keen thirst for scientific knowledge that so typifies CHAOS. Saturday morning on Pacific Tarn Expedition Day 2002 dawned bright and clear. We gathered at the McCullough Gulch trailhead, and Paul gave us a stirring speech:

Men and women of CHAOS! Today we embark on a mission - nay, a quest - to discover and explore the highest lake in America! What unknown dangers lurk ahead, we know not. What perils beset the trail, we know not. What hidden creatures lie concealed in the lake's frigid depths, we know not. All we know is that we go - and in going, we shall push back the veil of ignorance and superstition that has held one very small corner of the Tenmile Range in its pernicious grip! Never before has such a distinguished group of scientists been assembled! And if these valley walls and great mountain peaks should last a thousand years, if CHAOS shall still endure thirty generations hence; so shall it ever be said, that this was their finest hour!

And with that inspirational message ringing in our ears, we charged up the trail. We followed the Quandary Peak climber's trail about half way up McCullough Gulch, then angled off toward the northwest. There is a small rocky lake at 12,695 feet, well above treeline at the northwest end of the valley. The talus slope above this lake was the only difficult part of the hike in. At the top of the talus we knew there was only a small ridge to the north separating us from our goal, but where? We all crested the ridge at somewhat different points, and then Pacific Tarn hit us in the face with a visual Wham!

Wow! That's big! There was no doubt in anyone's mind that this is truly a lake. Pacific Tarn was bigger than I remembered. It fills a broad cirque below Pacific Peak, and presents quite a comfortable tableau in that jagged and mostly vertical setting. There is a rocky alpine meadow to the east and north, and we made our way to that obvious camping spot.

I hadn't come all that way not to go swimming in the nation's highest lake, and I figured after the hot climb up to the ridge my core body temperature was as high as it was gonna get. I wanna get The Full Scientific Lake Experience! So three of us quickly dumped our packs, stripped down to our skivvies, and plunged in! Yee-hah! Splash! Woo-hooh! That water is cooold!!!

[Note: A few weeks after we got back I started to wonder if we had introduced biological contamination into the lake by swimming in it. It's unlikely that we brought anything new - the lake has been visited by hikers for decades, and certainly some of them have rinsed their hands or soaked their feet in its waters. Nevertheless, to be on the safe side it's probably best not to go swimming in these high lakes.] We started taking measurements right away. I had brought along two thermometers: a small red-alcohol thermometer on a key chain, and a refrigerator thermometer. I placed them underwater at about 1 foot deep just off the north shore. After about 20 minutes (at 1:00 PM), the alcohol thermometer read 52 degrees Fahrenheit, and the freezer thermometer read 45 degrees F.

We figured that the most important measurement to take was the lake depth. I had brought along a 50-foot length of rope, and I tied a rock to one end of this. I marked 5-foot intervals on the rope with my tape measure and some masking tape, so we could plumb the depths and record each sounding. The water was clear enough but not stunningly clear. From the slopes above the lake we could guess at the deepest region by the water color. We blew up our two one-person rubber rafts, and I took one of them out onto the lake. I wore a life jacket and was tethered to Rom on the shore via a long length of parachute cord. We used the tether because if someone fell into the lake and froze up, we wanted to be able to assist them to shore.

It was really cool to paddle around in the lake at 13,420 feet, with the high peaks of the Tenmile Range all around and ice ledges along the shore! Although the surface of the lake was mostly clear of ice and snow, the snowfields along the southwest quadrant of the lake still extended down into the water. We had only brought along one paddle, and even with the best J-stroke it was hard to make that little raft go in a straight line. But we could get around, and it was fun! By following Rom's guidance from the shore, I managed to find with my rope a spot where the lake was 23 feet deep. This spot was somewhat to the southwest of the lake's center.

At 1:50 PM we witnessed a large iceberg calving event, the largest of three major calving events that we saw while we were there. A large snow shelf along the west shore suddenly broke off and slumped into the lake with a large splash! It sent a big wave across the lake. I was sitting in the raft about 100 yards away and holding onto shore at the time, and the wave was big enough so that I had to push off from shore to avoid grinding the hull on the rocks. A bit later I measured the broken-off shelf with my tape measure. It was crescent-shaped, about 10 feet wide and 60 feet long. The resulting iceberg did not float free as some others had done, but immediately grounded on the bottom and on some other ice that we could see greenly under water. By the time we departed at about 10 AM the next morning, the iceberg was completely gone.

Joey took a turn in the rubber raft next while I tethered him from shore. He had borrowed a portable sonar and fish finder unit, and we used this to determine the lake depth because it was easier than using the rope. Joey also had a GPS with him, and he called out waypoint numbers and depths as I wrote them down on shore. He found three points where the sonar reported a depth of 28 feet, and this is the maximum lake depth that we found. He verified the sonar reading with the rope a couple of times, and they agreed to within a foot. (Waypoints 11 and 12 have no depth because Joey was docked along the west shore adjusting something.)

| Waypoint | UTM-X | UTM-Y | Depth (in feet) |

| 1 | 403525 | 4364044 | - |

| 2 | 403428 | 4363937 | - |

| 3 | 403381 | 4364006 | 5 |

| 4 | 403396 | 4364001 | 15 |

| 5 | 403408 | 4363978 | 24 |

| 6 | 403414 | 4363975 | 26 |

| 7 | 403398 | 4363987 | 17 |

| 8 | 403438 | 4363926 | 21 |

| 9 | 403376 | 4363999 | 23 |

| 10 | 403409 | 4363928 | 14 |

| 11 | 403374 | 4363956 | - |

| 12 | 403376 | 4363953 | - |

| 13 | 403376 | 4363951 | 6 |

| 14 | 403416 | 4363953 | 14 |

| 15 | 403442 | 4363907 | 28 |

| 16 | 403450 | 4363898 | 26 |

| 17 | 403445 | 4363912 | 28 |

| 18 | 403426 | 4363942 | 28 |

| 19 | 403413 | 4363941 | 18 |

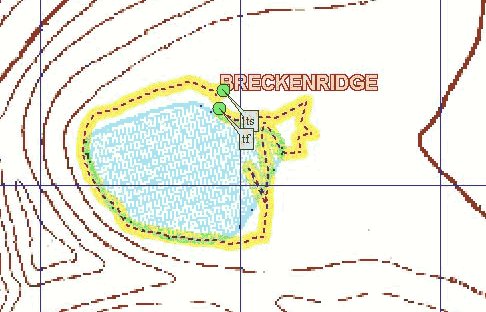

More measurements! We've gotta have more measurements! Joey brought my keychain thermometer with him in the raft, tied it to a short strap, and let it drag along with him in the water. The water temperature measured in this way was 54 degrees F just below the surface. After his stint in the raft, Joey walked around the shore of the lake, recording GPS waypoints as he went. These waypoints give us a fairly good picture of the outline of the lake. Paul cleverly graphed the shoreline waypoints superimposed over the official topo map to get an interesting picture of Pacific Tarn. As you can see, Joey did a little micro-exploring among the very shallow areas on the east side of the lake.

Meanwhile, I gathered a couple of water samples by reaching out off the north shore by our camp and filling a sterile sample bottle with clear water taken near the surface. About a week later, at home, I measured the pH of the sample with litmus paper at 6. This is slightly acidic, but well within the normal range for a lake.

By looking at the shoreline and the stains on the rocks, the lake appeared to be 6-12 inches below its highest level (we couldn't tell if that was also the normal level). Recall that spring and summer 2002 are the driest ever recorded in Colorado history. Pacific Tarn is interesting in that the area around it is flat, not a jumble of rocks like many high alpine lakes. There was lots of green filmy algae in the water near the outflow to the east. The lake water was not crystal-clear, but it was okay. We all filtered the lake water and drank it with no ill effects. There was substantial flow in the outlet stream, and thick peat moss in that area. The east side of the lake shore supports lush vegetation, including something looking a bit like microbiotic soil that I did not recognize. On the upper (west) side of the lake, by the snowfields, we could hear water gurgling under the rocks and flowing into the lake.

We did not see any sign of fish, minnows, snails, or crayfish. The only sign of animal life that we observed in the water was some little wormlike remains of larvae (?) near the north shore, attached to the rocks in shallow water. These were about a half inch long. Joey said that his fish detector icon on the sonar unit turned on once, but we never confirmed that.

The topo map does not show any stream leading away from the lake. The outflow stream passes through a broad shallow area at the eastern side of the lake proper, and one can easily walk across this area with watertight boots. The stream then collects itself a bit, making necessary a small jump if one crosses about a hundred yards farther east. Beyond that the outflow stream disappears under the rocks as the slope slowly gets steeper. There is no higher sill to the east of Pacific Tarn; the land simply and slowly falls away, finally getting abruptly steeper at the top of Spruce Creek gulch. From our camp on the north shore, we had to walk a long way to get any privacy!

The terrain and rocks indicate frost heaving in the flat areas beside the lake. There were a lot of flies buzzing among the rocks on the northwest shore, between our camp and the snowfields. They made walking in that area difficult. At 9 PM on Saturday evening we spotted three bats flying low above our camp, making good use of that bounty. Go, bats!

Most of our expedition bagged Pacific Peak on Saturday afternoon, but Mike and I were busy playing scientist and didn't climb the peak until early on Sunday morning. From the summit at 6:40 AM we saw another iceberg calving event on the lake - we happened to look down and spotted the circular waves spreading out from the ice shelf across the calm surface of the lake. Besides the big calving event shortly after we arrived, we had also seen another iceberg break off from the shelf early on Saturday evening. These three calving events alarmed us! While I realize that Pacific Tarn is not the Larsen Ice Shelf in West Antarctica, the frequency and size of the shelf breakup was surprising. At that rate, we figured that the over-water portion of the ice shelf would be gone in a week! Global warming right in front of us! Ice melts pretty fast in 54-degree water. (I've always wondered: How can there be an East and West Antarctica?)

A couple of us took the rafts out on Pacific Tarn on Sunday morning. We paddled untethered across the lake this time. Yesterday's breeze was gone, and we felt more confident. The most interesting area was along the ice shelf. The melting ice dripped into the water, and bubbles rose from underwater ice that we could see glowing green a couple of feet below the surface. We were careful to stay a few feet away in case another iceberg dropped off. Pacific Tarn is a little taste of Glacier Bay high in the mountains of Colorado! For what it's worth, I would advise those people figuring out how to penetrate Lake Vostok in Antarctica to drop the tether after their robot has melted through the ice. Jacques Cousteau found out long ago that a tether gives you a sense of security, but ultimately is more trouble than it's worth.

I still needed some photographic evidence that would confirm the size of Pacific Tarn and allow us to verify the size of the lake shown on the topo map. Before the expedition I had this horrible dream of standing before the Royal Geographic Society in London, trying to justify why Pacific Tarn should be called a lake. I remembered that the Society had doubted the existence of snow on Kilimanjaro in 1849, and I worried that a similar fate might befall me:

Royal Astronomer: Mr. Drews, in your earlier testimony you told us that Pacific Tarn is, and I quote, "really big", and "very big." Please tell this esteemed panel exactly how big is Pacific Tarn.

Carl: Well sir, it's big! I mean, we had a whole bunch of parachute cord tied together, and it didn't even come close to reaching across the lake.

Royal Astronomer: I see. How many meters is "a whole bunch of parachute cord"?

Carl: Well sir, we forgot to measure the cord exactly, but it sure took up a lot of space in Dan's backpack!

Paul: Your honor, I have a PhD in computer science and I can testify without a shadow of a doubt that Pacific Tarn was Big. Way Big! We're talking Huge here, eh??!!!

Royal Astronomer: Thank you, Mr. - er - Dr. Fearing, we appreciate your perspective.

Carl: It took us quite a while to hike around it. I didn't think of swimming all the way across! And don't even get me started on how hard it was to paddle that rubber raft with only one paddle!

Royal Astronomer: Mr. Drews, we are as eager as you are to push back the veil of ignorance and superstition that has held one very small corner of the Tenmile Range in its pernicious grip. But without accurate measurements this Society simply cannot justify to Her Majesty why your body of water should be designated a lake. Come back when you've got some meters or feet to report. This hearing is adjourned! }Bang!{

I woke up in cold sweat, screaming out loud for a thousand-foot inflatable table measure.

If I had a laser interferometer I could just beam it across the lake and write down the number. But cruder methods would have to suffice this time. Basically I wanted to lay down a gigantic yardstick next to the lake, take a picture from above, and calculate the measurements from the photo with a ruler. Although I didn't have a helicopter to hover directly over the lake, Pacific Peak looming above would make a good enough vantage point. All I needed was the yardstick.

With my 25-foot tape measure I measured away from the center of my tent, which was set up in our flat camping area on the north shore. I carefully spread out a white T-shirt on the ground 100 feet from my tent. Then I laid out a second T-shirt at the end of a second 100-foot measurement at right angles to the first. Now I had a right angle visible from above, with two 100-foot legs, next to the lake. I aimed one of the legs toward my expected vantage point near the summit of Pacific Peak, and the other was perpendicular to my vantage point. In this way I could obtain two orthogonal measurements of the lake, and estimate the surface area that way. There would be some parallax due to viewing the lake from an angle, but as long as I didn't mix up the horizontal and vertical measurements I would be okay. I took the following photo on my way to the summit of Pacific Peak at 6:30am on Sunday morning.

I have circled in red the center tent, and my two T-shirts. Of course the leg parallel to the viewer's line of sight looks shorter, but we expected that. The T-shirts just barely showed up in the early morning light, but you can make them out. I measured up to the obvious edge of the lake on the left, not including those tiny outflow ponds beyond the strand of rocks. (Notice that the calved icebergs from yesterday afternoon are completely gone.)

I worked with the original digitized image, which is 3x larger than the one posted above. The horizontal (left-to-right) leg measured 51.5 millimeters on my screen, and the vertical leg (top-to-bottom) measured 14 mm. So far, so good. Now for the lake. The horizontal distance across the lake at its widest point measured 288 mm on my screen, and the vertical distance measured 65 mm. Therefore we can conclude:

Horizontal span of lake = 100 * 288 / 51.5 = 560 feet.

Vertical span of lake = 100 * 65 / 14 = 464 feet.

Since the lake is fairly round, we can use those two numbers to calculate the average diameter, and calculate the total surface area from that.

Average diameter = (560 + 464) / 2 = 512 feet.

Average radius = 512 / 2 = 256 feet.

Surface area = pi * 256 ^ 2 = 205,887 square feet.

Surface area in acres = 205,887 / 43560 = 4.7 acres.

These measurements confirm the estimate of 5 acres made earlier from the topo map. All right! (And I didn't even have to take a single cosine!) One could probably get an even 5.0 acres by including those little attached ponds along the east shore.

To calibrate my temperature measurements I placed the two thermometers in an ice-water bath, which I knew would measure 32 degrees F when the ice and cold water were in equilibrium. The red-alcohol keychain thermometer read 35 degrees F, while the refrigerator thermometer read 24 degrees. By this time I was getting suspicious of the fridge thermometer, so I decided to eliminate those readings. Later I learned that bimetal strip thermometers are not very accurate. From the ice-water bath I concluded that the keychain thermometer was reading 3 degrees F high. So I subtracted 3 degrees from the raw reading recorded at the lake, and reported the adjusted real lake temperature below.

To test my water sample I used a WaterSafe drinking water test kit that I bought at a local hardware store. It was made by Silver Lake Research, http://www.watersafetestkits.com/.

Pacific Tarn measurements taken July 13, 2002

Measurement Value Altitude 13,420 feet Surface area 4.7 acres Maximum depth 28 feet Surface temperature 51 degrees Fahrenheit pH 6 Bacteria negative Lead negative Pesticide negative Nitrates/nitrites negative LR total hardness 0 Total chlorine 0 Latitude 39� 25' 10" North Longitude 106� 07' 10" West

One might think that Pacific Tarn is the highest lake in North America, but no! That honor belongs to the Mexican volcano Nevado de Toluca, which has two lakes in its crater called Lake of the Sun and Lake of the Moon. These lakes have an approximate elevation of 13,800 feet (4,200 meters). The peak itself is 15,196 feet.

There is some discussion about whether Pacific Tarn freezes solid down to the bottom during the winter. I don't think I would disqualify it from being classified as a lake on that basis, knowing that there are some "lakes" in the dry valleys of Antarctica that have probably been frozen solid since the Medieval Climatic Optimum. However, it's an interesting question. How thick do the high alpine lakes of Colorado freeze during a typical winter?

There would be some avalanche danger involved in trekking up to Pacific Tarn during the winter, but it could be done. Once you're there, you could either drill or chop through the ice and measure the thickness. 28 feet is about 3 stories high. I doubt that the lake freezes that thick, but is there is any hard evidence available?

Arctic ice freezes to a maximum draft of about 11 feet (the draft is the floating depth, the distance from the ocean surface to the bottom of the ice). So that's about 12-13 feet thick. But ocean water is salty, and freezes at a lower temperature than fresh lake water. The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) does not keep records of ice cover for alpine lakes, although they agree that such data would be interesting. There are extensive (and fascinating) records of ice thickness at various measuring stations in Canada at the following web site:

http://www.cis.ec.gc.ca/cia/icesnow.html

See what cool data you can find on the Web? For station YZF on Great Slave Lake at Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories, I found a maximum ice thickness of 183 centimeters (6 feet) on April 16, 1965. Even if the two situations aren't completely similar, 6 feet is a long way from 28 feet. The thickest measurement in that data set was 11 feet for sea ice. So I feel safe in concluding that Pacific Tarn does not freeze solid all the way down to its deepest point.

Nevertheless, I plan to ski into Brainard Lake in the Indian Peaks sometime this winter. Brainard Lake is at 10,345 feet. I will drill or chop through the ice, measure its thickness with a tape measure, and report the results back here. That should be closer to a comparable situation.

On March 8, 2003 I went to Peterson Lake at 9,300 feet near Lake Eldora Ski Resort instead. There I measured the ice thickness at 19 inches out in the middle of the lake. It took me 1 minute to drill a 5-inch-diameter hole through the ice with my new Strikemaster Lazer hand ice auger. That auger sinks into the ice like a hot knife through butter!

On March 26, 2003 I measured the ice thickness at Brainard Lake. The ice was 27 inches thick, under 34 inches of snow. The lake at my drilling site off the north shore was 82 inches deep.

On May 4, 2003 I made the trek again to Brainard Lake. My friends Nick Van Derveer and Brent Robbins came with me, and helped me drill the hole and take the measurement at the same site despite howling winds off the Divide. We measured 36 inches from the ice surface to the bottom of the ice, the thickest I've ever seen in Colorado. However, after drilling through about 10 inches of white ice on top we hit a layer of water about 4 inches deep. Below the water layer the ice was harder. So we have: 36 inches of ice coverage = ~10 inches of white ice on top + ~4 inches of water + ~22 inches of solid lake ice below. It was obvious to us that the two upper layers had formed over time from the 34 inches of snow measured on March 26. The total water depth measured in the hole was 79 inches deep, and the water came up to 3 inches below the ice surface.

On April 19, 2008 I measured the ice thickness at Bear Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park. We found: 10 inches of mostly dry snow on top, 5 inches of water-saturated snow below that, followed by 34 inches of hard ice. I had to use the longest extension on my ice auger! Simon Drews and I shoveled away the dry snow and slush down to the level of hard ice, leaving a pool of clear water five inches deep in the shoveled hole. Then we started drilling. The total water depth in the augered hole was 12 feet, measured down to mud on the bottom of the lake. That's some pretty thick ice!

On February 14, 2009 Simon and I returned to Bear Lake. We cranked the ice auger down and measured 27 inches of hard ice on the lake (2 feet 3 inches). The water depth at the hole was 11 feet, and there were 10 inches of snow on the ice. For the first time, there was no slushy watery snow on top of the ice. But the snow-ice interface was indistinct, as if a former slushy layer had frozen.

For independent confirmation, I checked the mountaineering guide book Colorado's Thirteeners, by Gerry Roach and Jennifer Roach, 2001. Here is what they have to say about "Pacific Tarn". This quotation is from section 4.7 Pacific Peak - Northeast Slopes *Classic*, on page 60:

Once on the plateau, hike 0.2 mile west and visit the amazing unnamed lake at 13,420 feet. Snowbound into August, this is one of the highest lakes in Colorado, if not the highest. From the lake's east end, hike . . .Roach gives the lake 20 more feet of elevation than I originally did, and he's probably right because the lake is above the 13,400-foot contour line on the topo map. If Gerry Roach doesn't know of a higher lake in Colorado, then there probably isn't one.

Despite numerous claims that "Tulainyo Lake is the highest lake in the continental United States," I wondered if perhaps some unnamed higher lake was lying undetected somewhere along the crest of the Sierra Nevada, having eluded the prying eyes of hikers and geographers. So I got a topographic map of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, and went over the High Sierras with a fine-toothed comb. The two major fourteener regions in California are around Mt. Whitney and North Palisade, so that's where a lake above 13,400 feet is likely to be. I did not find any lake higher than Tulainyo there, but I did find a small unnamed lake at 12,890 feet on the northeast face of Caltech Peak, near Mt. Stanford.

As soon as I finish this web page I plan to fill out the official form for proposing a new name to the United States Board on Geographic Names, and send it in. I will post the progress of that process here. It may require some public hearings and local publicity. Stay tuned . . .

February 9, 2004I believe this letter makes the story complete.

Dear Mr. Drews:

We are pleased to inform you that the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, at its January 8, 2004, meeting, approved your proposal to name an unnamed lake in Summit County, Pacific Tarn. This decision was made in agreement with the findings and recommendations of the Summit County Board of Commissioners, the Town of Breckenridge, and the Colorado Board on Geographic Names. The new name will be published in the Board's Decision List 2004, and has also been entered into the Nation's official geographic names repository, which is available and searchable online at http://geonames.usgs.gov. The entry reads as follows:Pacific Tarn: lake; elevation 4,090 m (13,420 ft); 5 acres; located in Arapaho National Forest, in the Tenmile Range, 0.5 km (0.3 mi) SE of Pacific Peak, 10 km (6 mi) SW of Breckenridge; named in association with nearby Pacific Peak; Summit County, Colorado; Sec 28, T7S, R78W, Sixth Principal Mer; 39 degrees 25' 10" N, 106 degrees 07' 10" W; USGS map - Breckenridge 1:24,000.Sincerely yours,

Roger L. Payne

Executive Secretary

U.S. Board on Geographic Names

Pacific Tarn is in the high alpine environment, where life clings to a tenuous existence during the short growing season. Be gentle. Don't pollute the lake or the surrounding rocky meadows. Don't introduce any fish or other organisms into the lake. Pacific Tarn has been isolated from the other nearby drainages for thousands of years, and the only natural transfer mechanism has been animals like birds and marmots. It's remotely possible that there are some interesting microbes in the lake, unknown to science, that have evolved there under the intense ultraviolet glare. You can study the lake, observe it, learn from it, and enjoy the serenity of its calm waters - but please let it live.

Special thanks to my friends Paul Fearing and Paul Riciputi, whose infectious enthusiasm turned a crazy idea into a scientific expedition! My warm thanks also goes out to the other members of the CHAOS carrying and measuring team: Michael C. Cole, Theresa Soutiere, Rom McGuffin, Mike Strasser, Pete Simpson, Dan Murray, Emily Reith, Valerie Hovland, Francis Joseph Mills IV (Joey), Matt Wentz, and Kate. Without you this would have been a slog-fest. With you, it was fun!

Photographer Mike Strasser took some excellent photos of the expedition, which you may view here:

http://www.greenradish.com/chaos/pacific_tarn/page_01.htm

Bill Mason reports:

I did a short dive in the tarn in August of 2011. It was an ultralight solo expedition, but I did the dive. Mostly I wanted to do it to see if I could pull off the logistics. The trip was excellent, with great weather and good conditions. The lake was really murky with what I assume to be algae. Visibility was about three feet at best. I'd like to return with more help carrying gear to do a proper expedition, take samples, photodocument the bottom, and do anything else that would be useful to the scientific community.

John Bali made a scuba dive into Pacific Tarn on September 7, 2013. His trip report has good pictures of the adventure: My Dive Into the Highest Named Lake in the United States.